Edan Alexander’s release was the last good news we’ll get from wartime Israel

I celebrated my fellow Tenafly native’s freedom. But there are too many reasons to believe the future for other hostages is bleak.

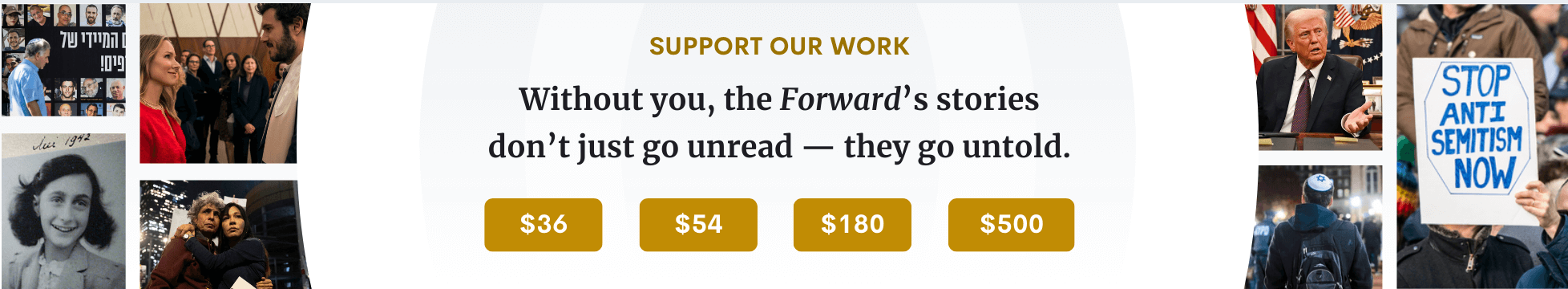

Hundreds of friends, family and residents gather in downtown Tenafly, New Jersey, to watch the release of Edan Alexander — the last living U.S. citizen kidnapped by Hamas — on May 12. Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Images

In my hometown of Tenafly, New Jersey, hundreds of us gathered Monday to celebrate a rare piece of good news: Edan Alexander, an American-Israeli hostage, was coming home. The crowd radiated unanimous relief — I saw it written across the faces of an Orthodox man wrapping tefillin on the former mayor; a Vietnam vet wearing a cross; a young mom dancing with her baby; and high school boys jumping in an impromptu mosh pit.

Yet this deliverance is not final. Not yet. Perhaps not ever. In the Jewish tradition of mingling hope and suffering, I listened to Einav Zangauker, mother of a hostage, Matan, who remains in Gaza, speaking on Israeli TV in the moments before Alexander’s release. The two young men were being held together, she said. Now, her son is by himself.

I wish that we could linger on celebrating Alexander’s return. Or on honoring the Tenafly community’s extraordinary support for Alexander’s family during the duration of his captivity, ensuring someone brought them food every day. But Zangauker’s words were a reminder: We don’t have that luxury. Even Alexander’s parents, as they rejoice in their son’s return, have already returned to advocating for the release of the rest of the 58 hostages who remain in Gaza, about 20 of whom are believed to be alive.

Looming over their efforts — and over all of Israel — is Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s catastrophic new war plan, which will expand operations with the aim of occupying Gaza. This disastrous strategy reflects the central contradiction of far-right Zionism, one that has increasingly dominated Israeli politics since the Second Intifada: Rather than saving the country, Jewish power is poised to unravel it.

In early May, Israel’s cabinet approved a new war plan, named Gideon’s Chariots. It involves calling up tens of thousands of reservists, indefinitely holding territory in Gaza, and forcing Palestinians to the south of the strip. The operation’s name is telling: In the Tanakh, Gideon is a righteous deliverer of the Israelites, who vanquishes a much larger foe with only 300 men.

The cabinet wants to frame this as a righteous, nationalist, underdog fight.

Leading up to the new plan, Netanyahu assured Israelis that this surge of forces will finally enable Israel to “achieve full victory in Gaza.” It’s a false promise he’s been making since Oct. 7. At its heart is a dangerous doctrine that’s been around since before Israel’s founding, and which went mainstream in the wake of the Second Intifada: the idea that Israeli power can guarantee security without the need for compromise.

Right-wing Israeli voices have long urged Israel to adopt more maximalist positions. For example, Netanyahu’s father, the historian Benzion Netanyahu, signed on to a 1947 ad that ran in The New York Times urging rejection of the United Nations plan that would create adjacent Jewish and Palestinian states between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea. “Either Palestine belongs to the Jewish people, or it does not,” the group running the ad wrote. “If it does, they are entitled to the whole of it; if it does not, none of it is theirs.”

For most of Israel’s history, however, its decision-makers retained the wisdom that the country needed to make concessions. David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s first Prime Minister, declared that “we will be ready to consider the question of a Jewish state in an adequate area of Palestine” even if “we are entitled to Palestine as a whole.” Prime Minister Menachem Begin, a founder of the Likud party — which Netanyahu now leads — dismantled settlements in the Sinai to secure peace with Egypt despite harsh criticism from his allies, such as the settler leader Rabbi Zvi Yehuda Kook, who slammed the Camp David accords as a “desecration of the sacred name of peace.”

What changed? The Second Intifada, a five-year stretch during which terrorists killed 1,038 Israelis in 138 suicide attacks that overlapped with my childhood years in Ra’anana, significantly shifted public opinion and the political calculus. It created a widespread sense of vulnerability, and undermined the already fragile faith some Israelis had that Palestinians could be trusted.

More importantly, it sparked a quest for safety through power and brute force.

To some extent, this quest for a security that didn’t rely on partnership with Palestinians, or a long-term resolution to the conflict, worked. The barrier separating Israel from the West Bank, which began construction in 2002, reduced terrorist attacks: The bulk of Israeli casualties in the intifada occurred before the wall’s construction. The Iron Dome — and subsequent military innovations — rendered Israel safer than ever from aerial threats.

For many, including some of my family in Israel, the years of violence in the early 2000s drove them toward the political right. “I remember being scared of going near a bus because it might blow up. Bibi fixed that,” a cousin once told me. That was a somewhat revisionist take: Netanyahu, after a stint as prime minister in the late 1990s, did not regain office until 2009 — years after the intifada ended. And yet I hear this sentiment, or variations of it, all the time in Israel.

As Israeli society turned right, the far right came to gain increasing influence. And that movement has always sought Jewish domination — the kind that says, “Why compromise when we have power?”

What many of the voters who shifted rightward didn’t reckon with was the extent to which this philosophy has emerged as a far greater threat to Israel than our external enemies.

It fed a central delusion that allowed the terror attack of Oct. 7 to happen: that bolstering Hamas to prevent unified Palestinian leadership was strategic, because we were powerful enough to avoid any consequences.

The new war plan escalates this kind of delusion to new heights. There is no victory in subjecting Gazans to a new slate of horrors; the IDF’s own officers are increasingly admitting that Palestinians are on the brink of starvation. There is no triumph in risking the fate of the hostages, whom the Netanyahu-government appointed head of the IDF said may die within days of the new operation being launched. Or in calling up tens of thousands of exhausted reservists, and continuing to bleed the economy dry in the process.

Neither security for the living nor solace for the dead will be attained by splintering Gaza into ever-smaller pieces of rubble. No future will exist for a country that abandons citizens like Matan Zangauker.

The Second Intifada shook Israelis’ sense of safety and shifted political attitudes to the right. Now, that shift has led to a crisis within Israel, as the destructive force of the far right’s gains becomes excruciatingly clear.

Some reservist soldiers who dropped everything to fight for the country after Oct. 7 now openly argue, as one of them did in the Israeli news outlet Walla, that “it’s legitimate to refuse a war whose stated goals are a complete lie. It’s legitimate to refuse a war that is our moral low point as a country.” Many more agree, if less vocally, and are not showing up for duty.

What does the security of Israel look like without the buy-in of its soldiers? Or without the support of the United States, which has reportedly expressed to mediators its opposition to Gideon’s Chariots, and is pressuring Israel to shift its negotiating stance, only to encounter Netanyahu’s intransigence?

I’ve never met Edan Alexander, although my mother knows his. And yet my heart caught in my throat watching his release. It reminded me that Israel is a country, a people, worth fighting for. Gideon’s Chariots is not the way to wage that fight. Certainly not for the hostages — whose freedom is reportedly last on the list of the operation’s military priorities.

There’s another key part of Gideon’s story besides his military prowess: After victory, he declines to remain in power. Netanyahu, Israel’s longest-serving prime minister, who faces criminal charges for putting his interests ahead of the country’s, is no Gideon. Just as Gideon’s descendants reaped the virtues of his humility, generations of Israelis will suffer the sins of this current government.