A pocket guide to the Jewish grandmothers of Mexico

David Caldreon Zonana’s ‘Pocket Abuelitas’ honors the legacy of Mexican Jewish matriarchs

David Calderon Zonana with an array of their “Pocket Abuelitas” zines. Photo by Sam Lin-Sommer

David Calderon Zonana is turning into a grandmother, they tell me. They laugh as they describe how their apartment is starting to resemble a grandmother’s. Their style of dress. Some of the recipes they cook.

We are chatting about Mexican Jewish matriarchs in a sunlit, plant-filled patio tucked between two old buildings. Calderon, who uses they/them pronouns, wears large, rimmed glasses and a navy blue shirt with a white drawing of a swordfish emblazoned across the front. A flat brimmed hat hangs off of the back of their neck by a drawstring.

In this cafe in Mexico’s City’s historic center, Calderon has already shown me plenty of grandmotherly concern. They have asked me whether I need any coffee, whether I might want to move to another cafe with more table space.

In the last few years, Calderon has spent enough afternoons chatting and cooking with Jewish abuelitas to produce 20 zines, each one an ode to another matriarch.

The zines are part of a project called “Pocket Abuelitas,” a series of interviews and photographs with grandmothers in Mexico’s diverse Jewish community. “Abuelita” is a Spanish term of endearment for “grandmother.” For each book, Calderon cooks with a grandmother in her home while interviewing her about her life, family and cooking.

Calderon, 26, prints the booklets independently, and is going to sell them at their first book fair soon; but in the meantime, fans of Mexican Jewish grandmas can check out the zines on the project’s Instagram page. The page has already generated an online following, and the project has helped launch a television show on Canal Once, a local broadcast channel, that will feature Calderon interviewing Mexican grandmothers of all stripes.

I met Calderon through mutual friends when I was looking for a guide to Jewish Mexico. We met up in a cafe in the city’s historic center just before Calderon was scheduled to lead a tour with Sinagoga Justo Sierra, the second-oldest synagogue in the city. As Jewish diaspora nerds, we had plenty to talk about.

“There is a big connection with our grandmothers in the Sephardi and Syrian Jewish communities in which I grew up. Twice a week we would eat, all of the extended family, in my grandmother’s house,” they said.

“In general, Mexican culture is very family-oriented. You add Judaism to that and it’s just like family on steroids.”

True to the project’s name, the colorful booklets that Calderon makes are small enough to fit in one’s pocket. The books showcase a Mexican-Jewish world that is more pluralistic than its American counterpart. Interviewees are mainly Mizrahi and Sephardi, with roots in places like Syria, Morocco, Greece, and Turkey, as well as in Ashkenazi centers like Poland and France.

The book’s culinary photos are a delicious tour through the Mexican-Jewish diaspora: squash in tamarind syrup; eggplant burekas; “Turkish eggs” that Clarisse Meschoulam, one of the featured abuelitas, told Calderon she would serve with chilaquiles (fried tortillas bathed in salsa) on Shabbat.

The interviews and recipes are recorded with line breaks and indentations that render them into poetry. Chela Nissan, whose parents immigrated to Mexico from Istanbul, Turkey, and Salónica, Greece, introduces her chicken meatballs by saying, “they took us out of our problems / because the meatballs / you would take them / and put them in the soup / in the tomato broth / in whatever you had / and they would bring us out of the struggle.”

Calderon learned to make zines while working at Gato Negro Ediciones, an experimental printing house. They grew up in a Modern Orthodox family that straddled the city’s Sephardic and Aleppan Syrian worlds, and at 18, they moved from the suburbs to the city, where they promptly fell in love with the bustling historic center where many Jews once lived, worked and prayed. Five years ago, they started leading tours with La Sinagoga Sierra Justo, where they take visitors through the plazas and narrow streets of the historic center, with a focus on the massive Merced market, where many Jewish immigrants found their footing in Mexico.

Speaking in English — Calderon has spent significant amounts of time in the U.S., and their maternal grandmother is a native New Yorker of Egyptian heritage — we chatted about grandmas, kosher tacos, multilingual slang, and why Jewish Aleppo is as mythical as pre-Hispanic Mexico City.

This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

How did this project come to be?

It’s going to be hard for me to talk about my grandmother, because she passed away less than a year ago. I have a very very close connection with my grandmother —my dad’s mom. I could spend hours and hours just hearing her talk, and she would love telling stories.

She was born in Casablanca, Morocco. Her parents were both from Turkey. She lived there throughout World War II and then arrived here in Mexico when she was only 14 years old and started working straight away with her dad, like most of the immigrants, in the jewelry district.

I would tell her, like, “Hey grandma, I want to make a book about you.” She’d say things like, “No, why? I’m just a normal person.”

So instead, I was like, “Hey Grammy, can you teach me your recipe?” She was like, “Yeah, of course, come tomorrow!”

So I went with her, and while we were cooking, I asked questions, and she told me things. And I left my recorder on, and I started taking pictures of her spoon collection, her old pictures, her sweater, things that to me are part of her spirit, you know?

After doing it with my grandmother, I realized I could do it with any grandmother. So I started reaching out to her friends.

Within five minutes of meeting any of these grandmothers, I feel like they’re already treating me as if I was their grandson. Which is very touching for me. I feel like it’s a hug in the wound of my grandmother’s passing. Now I feel like I have many grandmothers.

I feel like this is a very Mexican project too, in the sense that we are a matriarchy in Mexico. My father hates this, but I always say, “We’re all Guadalupa here.” Even Jews. To me, the Virgin of Guadalupe just represents the divine mother. In Mexico we worship the figure of the mother in all aspects of life, and I grew up worshipping my mother and my grandmother.

The text in your zines is written like poetry, with line breaks and without punctuation or formal grammar. Why is that?

It’s not written, it’s spoken, right? I’m just putting in the space here the way the words of my grandmother sound in my head. I feel like poetic language in many ways ties into a different type of language. It’s not necessarily pretending to be official, to be correct, to be rational, you know?

In the Spanish speaking world in general, there is a big movement of resisting against grammar, because unlike English where you have different institutions that regulate grammar, in Spanish, everything is regulated by the Real Academia Española.

I don’t want to ask permission to transcribe my grandmother from a colonial institution that is based in Spain. In many ways, the way my grandmother speaks has never been looked at by academia.

We Jews here, we use a lot of expressions that are not even Mexican. They come from Arabic, from Ladino, from Turkish.

In the U.S., Ashkenazi people tend to dominate the Jewish cultural sphere. What would you say it’s like here?

Every Jew will probably give you a different answer.

As in the United States.

But no, I don’t feel like any of the communities dominate here. In Mexican Jewish slang, we use words from most of these Jewish languages that you can hear. So even Syrian Jews, when they say here, “I have to go pee,” we say, “Tengo que ir a pisar.” I have to go pissing. That comes from Yiddish.

Even Ashkenazi Jews use a lot of Arabic expressions. Like to say “poor things” they’ll say, “hasito” or “haram.” Ladino, a bit less. I can only think of one word, that is when you invite yourself to a plan. It’s called “encasharse.”

And also we use religious Hebrew. We don’t say “oh my God” or “Díos mío,” we say “Shema Yisrael.”

How did you meet the other grandmothers you talked to?

I started with my grandmother. And then her best friend. And then with these two, it was very easy to start what I call “grandmother networking.”

And everywhere I go, I show people the zines, and people are like, “Oh, you have to interview this person!” Everyone has a grandmother that has something [to share].

I interviewed Miss Flora Cohen. She’s more than 100 years old. She’s like the Julia Child of Syrian Jews. She’s written so many recipe books, not only of Syrian Jewish food. She’ll make menus where, as a starter, there will be kibbe, which is very Syrian, but then baked Alaska for dessert. Like, it’s just all over the place, which is, I think, what we are.

How do grandmothers react to you wanting to hear their family’s immigration stories?

I think most of them really like talking about their stories. I have this feeling that a lot of these people have never been really interviewed a lot about their lives. So this is also a way of honoring them, you know? Because, in general, men have always gotten the spotlight.

Many of them, when I ask them questions, they’ll be like, ‘why are you asking me this? Like who cares,’ right? And I’m like, ‘Many people care.’

The world that I’m trying to revive through their stories is not necessarily even Jewish Syria, which, yes, I would love to be able to revive. It feels to me as mythical as pre-Hispanic Mexico. When I think of Aleppo, it feels like I’m thinking of Tenochtitlan.

What I want to revive is a Mexico that I feel I didn’t know but I want to know and I’ve been constantly trying to recover. Which is a Mexico where the Jews lived here, in these streets in El Centro, in the Roma, in the Condesa, in the middle of the city, where our neighbors were other Mexican people, and we shared the streets, and food, and stories.

I grew up in a sort of Jewish bubble in the suburbs.

So is the story of Mexican Jews right now no longer taking place in the center of the city?

No, it’s probably similar to how you grew up in the suburbs in the U.S.

I asked my grandmother, “What was it like living in Mexico City in the 40s, in the 50s? How were the streets? How were the people?” I want to recover that. I don’t want the same thing that I feel happened with the Syrian Jewish world to happen with the Mexican Jewish world.

For me, it’s so important to take care of our immigrant history here. It’s not only about Jews. It’s about Mexico. That’s why I always put [at the end of each zine] “sus recuerdos y sus recetas son parte del legado de la inmigración en nuestro país.” Her recipes and their memories are part of the legacy of immigration in our country.

What I’m trying to show with this project is that these grandmothers are very Mexican. Their expressions are totally Mexican. My next zine is about a great aunt from my mom’s side who’s Syrian but was born here. She taught me how to do tacos de canasta. They are, like, maybe the most central Mexican food you’ll ever find, right? But hers are kosher.

I want to celebrate how migrants are also part of this city. Even the founders of the city, the Aztecs, the Mexicas, they weren’t from here. Most people in Mexico City are descendants of migrants from other parts of Mexico.

Were there any moments during the interviews that really surprised you?

What surprises me is how Mexican everything feels to me. I don’t think of it in a nationalistic way. For example, I interviewed a grandmother named Ruth two weeks ago. She taught me gefilte fish a la Veracruzana, which was a very funny dish. It’s gefilte fish drowned in a salsa from the state of Veracruz. It’s totally fusion food.

She was born in Cuba, but she grew up in Queens, New York. She speaks Spanish with a sort of American accent, speaks a lot of English, she’s very much American, but she uses so many Mexican expressions I love, like “chamaca” or “chole,” which means, ‘I’m tired of this.’

Do you want other people to get involved in the project?

I would love people to ask me to interview their people in other parts of the world. In the Jewish community, and outside of it.

But what I would love is for more people to do it. I think it’s very easy to do. I take pictures and record the interviews with my phone.

How did you transcribe the grandmothers’ recipes?

They don’t cook in a very academic, or formal way. It’s like, you put a little bit of that, and a bit of this.

How would you write that?

Just like that. “A bit.” People will have to figure it out.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Fast Forward Ye debuts ‘Heil Hitler’ music video that includes a sample of a Hitler speech

- 2

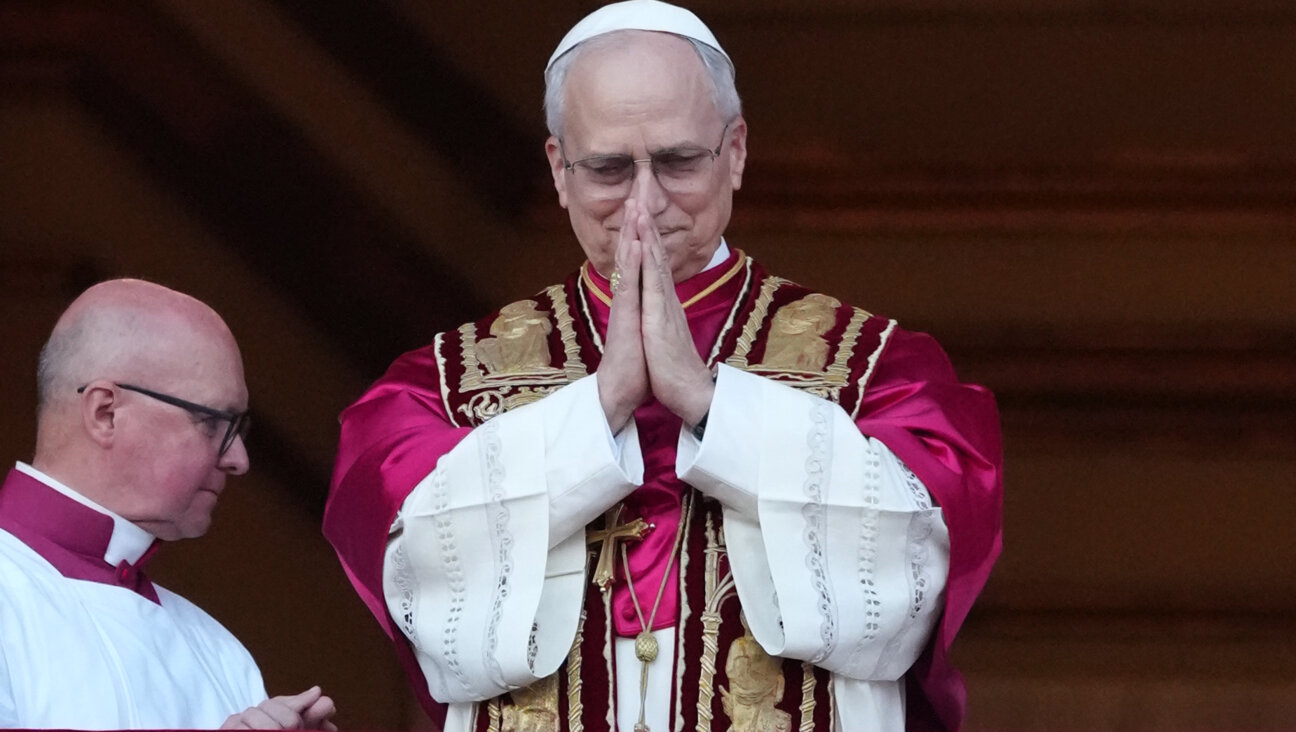

Culture Cardinals are Catholic, not Jewish — so why do they all wear yarmulkes?

- 3

Opinion It looks like Israel totally underestimated Trump

- 4

Fast Forward Student suspended for ‘F— the Jews’ video defends himself on antisemitic podcast

In Case You Missed It

-

Opinion It looks like Israel totally underestimated Trump

-

Fast Forward Betar ‘almost exclusively triggered’ UMass student detention, judge says

-

Fast Forward ‘Honey, he’s had enough of you’: Trump’s Middle East moves increasingly appear to sideline Israel

-

Fast Forward Yeshiva University rescinds approval for LGBTQ+ student club

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.